|

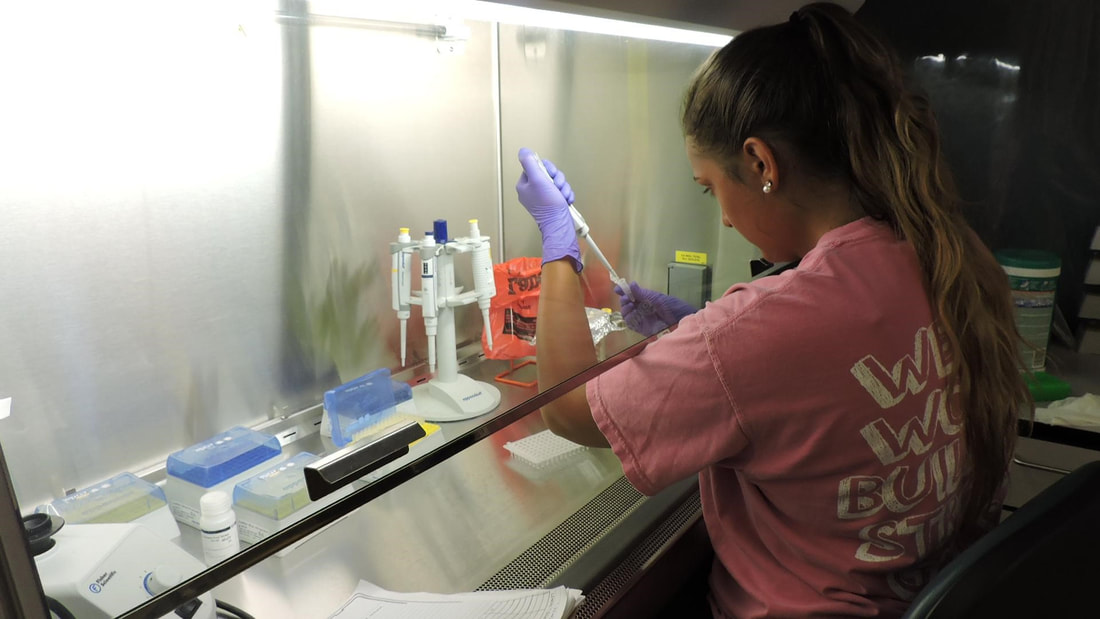

Blog Post By: Skyler Klingshirn (Summer Sea Turtle Intern) Here in South Carolina, we all know that our sea turtles face threats of being disoriented due to white lights, pollution on the beaches and in the water, as well as predation by raccoons, ghost crabs, and other animals. However, in other parts of the world, sea turtles suffer from a disease called fibropapillomatosis (FP). This debilitating disease causes the development of tumors on the body, eyes, and even mouths of all seven species of sea turtles and is associated with the virus Chelonid herpesvirus 5 (ChHV5). While the tumors are not cancerous, if the tumors get too large, they can prevent the turtle from swimming, seeing, eating, possibly leading to death. While the cause of this disease is still not for certain, it is believed that it has developed due to anthropogenic factors and pollution. Many of you may have not heard of this disease before, but that is because it is not common here in South Carolina. Most cases of this disease have been reported in warmer, tropical waters, such as off the coast of Florida with the first case being reported in the Florida Keys in a green sea turtle. This is an example of what fibropapillomatosis can look like. Last summer, I had the opportunity to research this disease at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute (HBOI) located in Fort Pierce, Florida. At HBOI, I was a research intern and lived in Fort Pierce for 10 weeks. With the guidance of my mentor, we took tumor samples from green sea turtles (Chelonid mydas) and loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and were able to extract the DNA from each sample. After we had the DNA from each tumor, we were able to make multiple copies of the DNA through a process called polymerase chain reaction, or PCR. We were able to input our findings into a database that helped us compare the strands of DNA we found to DNA from other FP samples. The virus associated with this disease, ChHV5, has four different variants in Florida, variant A, B, C, and D. Using this database, we were able to identify which variant of the virus each turtle had. We were also able to determine the viral load of each sample. We used this information to find relationships between the morphology of each tumor, the species of sea turtle host, and the variant of the virus. Here I am preparing a tray of samples to quantify the viral load. After 10 weeks of research and learning many new skills, I was able to present my findings to the rest of the interns and staff at HBOI. Unfortunately, the study is still going on and I am unable to share our results, but my experience at this research institute was extremely beneficial. I learn a lot of new things about genetics, microbiology, sea turtles, and the process of completing a research project. I gained valuable research and communication skills that will help me in my future career. Even though this is not a problem our sea turtles here in South Carolina face, I find it valuable to be aware of other happenings around the world. Hopefully one day soon, we can find an end to this disease, along with white lights and pollution.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Leah SchwartzentruberSea Turtle Biologist Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed